Blog 3

Is that which is true merely a matter of our unique opinion, or is it something more objective that each of us simply possess our own opinions about pertaining to the matter? Since there is matter, and since there are our opinions, how do we know which lays claim to the title of being “right” over the other?

Let’s get back to that question of objectivity and subjectivity in a bit.

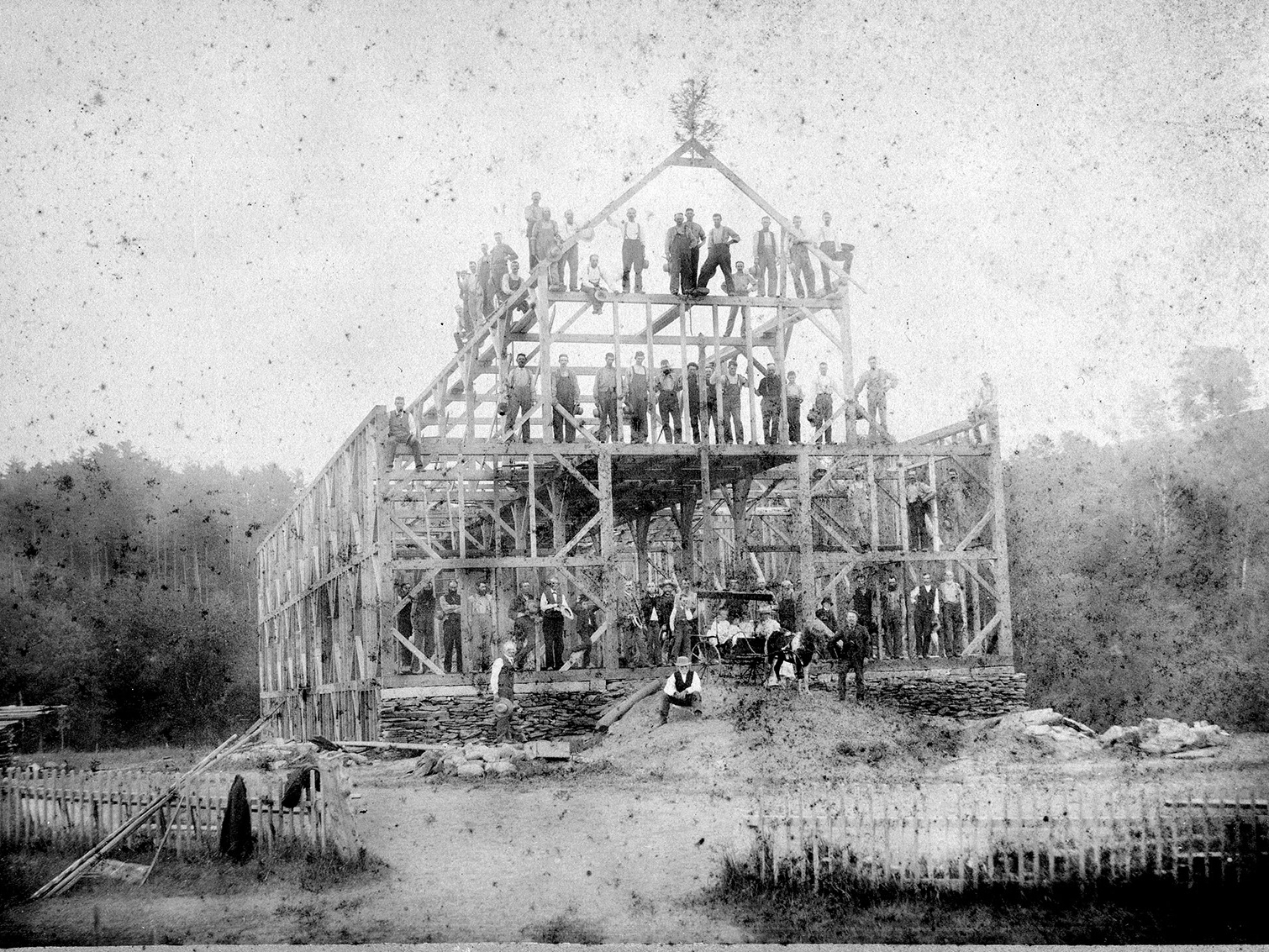

As progress has been made in the building of the BMDF site model, many techniques have been utilized along the way in an effort to strike a balance between modeling with an end goal of identical realism, and modeling with an eye towards approximating the essence of the place. One technique to quickly and successfully bring the model within the ball-park can be found in the software, SketchUp, and this tool is referred to as Photo Match. This neat tool allows you to import any photo you would like, thereby setting it as a fixed backdrop within your 3D model. By having this photo locked behind your scene, a perspective grid can be aligned to the photo, which relates it to the dimensional forms of the model space that is being drawn in. Put another way, this tool allows you to draw in perspective directly onto the photo, all while retaining the three-dimensional user coordinate system (UCS) of the SketchUp model. As you might already be envisioning, this carries tremendous value for the field of historic preservation and especially for the modeling goals of this project – along with many other similar projects which heavily rely on available photography to inform one’s understanding of a cultural landscape. By using this feature of the software in a creative way, I am able to assemble pertinent details of known views within the digital model in such a way that forms a more thorough and precise representation of the landscape features in their historical conditions. Plus, there are a few bonus dimensions to this cool feature that were intriguing to discover…

SketchUp’s Photo Match tool also allows for guide lines to be projected from the perspective of the “camera” position outwards onto the SketchUp scene to intersect with the model at user-specified locations. This function proved useful in the process of marking edges of building corners or window dimensions, thereby providing an anchor point within the scene at exactly the right place to begin drawing from as I crafted a more accurate rendition of the particular building piece. However, by leveraging the potential of this function in its inverse (viewing from the model back towards the viewpoint), we can do what I conceptualize as reverse-photogrammetry – the process of identifying the actual vantage points and locations of the person who took the photo in the first place. By doing this, we come that much closer to confirming historical facts which were previously unknown (or were at best, estimated approximations) – namely, that we can better know things like where the famous photo from Dingleton Hill was captured! Being able to identify this kind of location-based information could lead to informed park planning, such as trail design and vista management to access the view, interpretive signage with a photo kiosk displaying a copy of the original photo, or even retaking contemporary photos of the landscape to compare change over time. The discovery of this kind of information typifies the goals for using exploratory methods within this project, through which, we learn from the model itself in addition to the novel techniques and software workflows that are leveraged throughout the process.

Much of the overarching desire to model this particular historic landscape is to fill in various gaps of research and understanding that we currently retain due to a limited collection of archival data and a deficiency of preserved photos, surveys, plans, or visuals that would have depicted the site in a previous time. To reiterate, the project’s vision and scope is to identify connections between the site history and its integral relationship with the landscape character. In order to accomplish that without such reference material, another area of exploration (in light of the landscape undergoing major structural changes over time) has been to engage in a variation on the “photo match” method but rather in plan view. To do this, I manipulated a digital elevation model (DEM) by means of referring to a historic aerial from before the River Road/NH Route 12A redesign took place in 1959. This major shift altered the eastern slopes of the farm site which bordered the BMD Pond. As a landscape architect, I am trained in the process of regrading a site by using the contour lines of a topographic survey in an effort to manipulate the landform from one configuration to another. However, the simplicity of software plugins like Geographic Imager (which works within the Adobe Photoshop interface) afford me the opportunity to “paint” and massage the landscape in more of a sculpting technique – taking after Augustus Saint-Gaudens himself. This technique of remolding and shaping the land with brush strokes and Photoshop clone stamp tools became the driving mechanism by which I rearticulated a DEM dataset (extracted from 2015 LIDAR data) into a representative form of the 1917 landform – all while referencing the aerial perspective photograph that was flown in 1939 from 30,000 feet in the air.

It truly is amazing what the simple act of capturing a unique perspective in photographic form grants from one human to another, and most notably for people who possess an inquisitive eye to see beyond the photo. Even as we assess matters this far down the timeline of human history – following in the stream of technological innovation that has given us insights which allow historic views and lost vistas to be revisited decades or even centuries later – it is unfortunate that some in our culture show disdain for objective facts or the truthfulness of history that actually took place in time and in real places. The existence of centuries-old structures stand as stalwart reminders opposed to these objectors, by testifying to the real lives and real work of those who came before us. Their view of life is evident in whatever writings they may have left, but also in these remnant artifacts that embody their living on the land itself. If nothing else, we share this connection with our forebears: not only that we all certainly hold our own opinions on matters of life and society, but that all the while, we share in a set of mutual surroundings that give context and a semi-constant sense of stability to each of us – albeit buildings, forests, ponds, soil, birds, or ultimately the mere ability to experience it all, in part. It is our perspectives which carry a great weight in representing a lived experience, and that thought has been interesting throughout this step of the project aimed at exploring perspective. I can’t help but think about stepping into the shoes of the some late 1800’s photographer as they made their way around the Blow-Me-Down Farm property snapping flash-bulb photos of the lot, at the request of Charles C. Beaman himself.

I have come to the conclusion that this modeling project inherently embodies one of the key principles of historic preservation, much like that olde photographer did. A preservation principle which stipulates that it is the active and present duty assigned to each generation to capture the present while maintaining history, and to do so by curating its collective value for future generations to appreciate. In other words, the process of modeling this historic landscape consists of the active task of formulating a novel method of doing things building upon a fixed standard of the way things ought to be done. In this case, the photo match represents the set standard – fixed in the past with an objective reality associated to its displayed features – meanwhile, the interpretation and representation of that site is crafted in the present. And, all of this, in due course, will ideally be for the future use of those generations yet to come. To those who can look back on what we are doing now, standing on our shoulders, and ever reaching higher because of our perspectives and labors. I feel inspired to take more pictures than just selfies now, how about you?

Thanks for reading,

Connor

Connor